Response: Executive Summary to Men’s Health Strategy Call for Evidence

Given the role of CPRMB in being an interface between research and policy implementation, this submission is based on how the men’s health strategy can be delivered by government, policy makers and the health system.

Alongside improving men’s health, the strategy’s other primary value is that it is a generational policy and practice change. It will embed men’s health as a formally recognised discrete and official field of professional practice, health research and public policy.

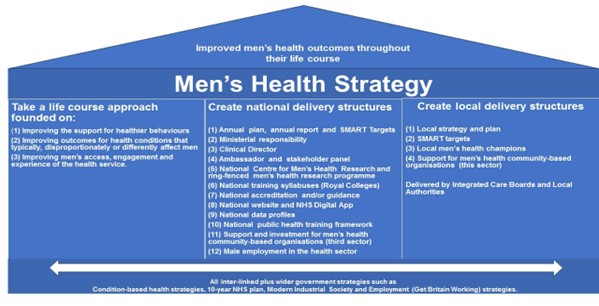

The CPRMB has focused more on macro-level system/structural “what works” process and infrastructure. That is overarching system-level, structural and relational solutions rather than discrete condition-based or life-course approaches (albeit condition-based and life-course approaches should be applied, where needed, in delivering some solutions). This will ensure the three DHSC men’s health delivery pillars succeed (healthier behaviours, outcomes and access/engagement/experience) as well as leading to wider policy and practice change.

The core delivery model for this structural change is based on the three core DHSC pillars and then building the national and local delivery structures and systems within and around them. The CPRMB response to the call for evidence is to focus on these national and local structures and is modelled below.

The current structure that is delivering the Women’s Health Strategy has been shown to be a success, and therefore there is no evidence to suggest that this would not work for a Men’s Health Strategy as well.

| Women’s Health Strategy | |

| Minister for with named responsibility | ✔ |

| Clinical Health Director | ✔ |

| Ambassador | ✔ |

| Health Champions | ✔ |

| Health Hubs (or equivalent) | ✔ |

| NHS Website | ✔ |

| Gender-health accreditation | ✔ |

| Medical Licensing Agreements (gender-health training) | ✔ |

Based on the evidence of what is working in women’s health alongside evidence of male-specific needs, the following are the proposed national level delivery structures for a Men’s Health Strategy.

(1) Annual Plan, Annual Report and SMART targeted goals: Underpinning the Men’s Health Strategy’s aim (a life course approach which takes into account intersectional issues), requires an annual plan, an annual report and a longer term (five year) yet small number of achievable SMART targets and goals. Examples are provided. It is vital to be able to see and measure “what success looks like”.

(2–4) National Leadership and Accountability Structures: There should be clear leadership and accountability for delivering the Men’s Health Strategy. This includes Ministerial responsibility, a clinical director and an ambassador.

(5) National Research Centre for Men’s Health (NRCMH) and Research Funding: There should be a national research centre for men’s health, ideally run by a university (not a charity/brand – to ensure independence and a broad research remit).

Alongside this, there should be national ring-fenced research funding within the NIHCR and ESRC focused on men’s health. This should also include research on how specific social determinants (aligned to the Marmot Review) act as compounding factors which will then support implementation across the whole of England and in all communities.

(6) Men’s Health Syllabus: There should be a general syllabus on men’s health in all of the Royal College’s health qualification programmes to ensure a better understanding of men’s health and life experiences. This will help deliver the three core pillars of the health strategy. The NRCMH would also work in partnership with Royal Colleges to create the syllabus.

(7) Accreditation System and/or Guidance: The Women’s Health Strategy states, albeit it is unclear if this has been implemented, that there would be a women’s health accreditation mechanism. If developed, an aligned mechanism should be in place for men’s health.

In addition or alternatively, DHSC should produce guidance (through the NRCMH) for the healthcare sector on how to deliver services that effectively supports and engages men.

(8) National Men’s Health Website and Digital App: The government should produce a central website on men’s health aimed at men – especially as men seek information online often before they reach out to the health system (“try before they buy”). The current women’s health website is a good example.

The NHS digital App will be a clear leap forward. However, the content, presentation and accessibility/navigation for conditions that differently or disproportionately affect men must ‘speak’ to men in a way they will respond to. Male health stakeholder groups will help.

(9) National Data Profiles: NHS Fingertips (an excellent resource) should be better promoted and be able to produce a clearer snapshot of men’s health including intersectionalities. This could be developed in partnership with the NRCMH.

(10) National Public Health Programmes Framework: A national funded training framework should be created to ensure men’s public health training is available to all statutory services, employers and health third sector organisations. Monopolistic provision should be avoided.

(11) Support and Investment in Men’s Health Community-based Organisations (third sector): The rise of men’s health community-based charities has been a significant success. However, funding may be precarious so the Government should review the resilience, research and consider providing some targeted funding for this sector without absorbing them into the ‘state’.

(12) Male Employment in the Health and Social Care Sector: There should be targets for increasing the volumes of men working in the health and social care sector as there is a clear gender gap. This would help support better representation, broadening of ‘male’ careers and address health staffing shortages.

Local replication

The above should be replicated for each Integrated Health Board and Public Wellbeing Board plus local condition-based strategies to have a gender lens. This would ensure there were no siloed strategies on specific conditions that did not link into a local men’s health strategy and vice versa. It would ensure men’s health is embedded into all strategies and operational delivery of health in each area and fully allow for local social determinants to be addressed.

Linkage across to other strategies

This strategy should be explicit in stating how it links into other government strategies such as the NHS 10-year plan or health condition-based strategies. More widely, it also should be clear on how it links into government’s Modern Industrial Strategy and the Get Britain Working Strategy.

July 2025