Missing Men: Men and Boys' Scorecard Report (Download)

Executive Summary

Too many men and boys in the UK are missing. They are missing from the economy. They are missing out on education. They are missing from society and families. To flourish, our economy and society need the energy and skills of men and boys and women and girls.

As our new “Missing Men Scorecard”, shows, men and boys have not fully recovered from the Covid-19 pandemic. Their life chances have been stunted; their lives remain less than fulfilled, they lead less healthy lives and their contribution to family and society has not fully gone back to a ‘pre-pandemic normal’. Indeed on many indices things have got worse.

This is because in a number of key areas, using the latest official data closest to the start of the pandemic (2019 or 2019/20), the scorecard shows:

• Employability is lower – with higher numbers of unemployed young men (251,000) and men in general, higher rates of inactivity, higher numbers of men wanting to work but are unable to because of long-term sickness (359,000) as well as falling employment rates (80.2% in 2019, 77.7% in 2024).

• The UK government has stated in its Get Britain Working white paper that it wants to achieve an 80% employment rate. Such an employment rate would make the UK among the highest performing countries in the world alongside Switzerland and the Netherlands. By our calculations, hitting this target would require a male employment rate of 83%, assuming that the gap in employment rates between men and women remains at the 6% difference seen since the pandemic. This would mean almost a million (975,000) working age men moving from unemployment or economic inactivity into work, to hit an employment rate last seen in early 1981.

• This is a demanding but worthwhile goal for public policy. Bumping up the male employment rate to 83% would mean an extra £22 billion in wages even if all the newly-employed men worked at the minimum wage; it would also raise £1.88 billion in income tax and £753 million in National Insurance contributions. Most strikingly, an increase in male employment of this magnitude would expand GDP by nearly 1%.

• Given the barriers to work faced by men it is worth the government ensuring that welfare to work policies are suitably gender sensitive; locally-based; and interlocked with its growth and industrial strategies.

• Male suicide rates have increased (14% increase in Wales and 2% increase in England since 2019) with England’s male suicide rate being the highest this century. Over 5,000 men died by suicide in Britain in 2023. That is three times the number of people killed on Britain’s roads in the same year. Suicide remains the biggest killer of men under 50.

• Life expectancy for men in England and Wales fell by six months between 2017-19 and 2021-23.

• Whilst there have been improvements in English prostate cancer and overall cancer mortality rates, the annual number of cardiovascular disease mortality deaths for those under 75 has increased by over 3,000 since the pandemic: from 63 per day in 2019 to 72 in 2023.

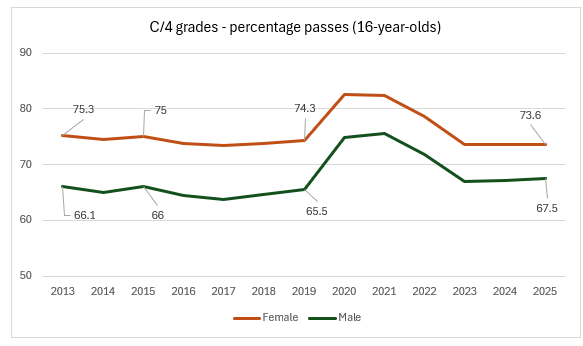

• There have been small improvements from the pre-pandemic period in some education results, but there are fewer male primary school teachers and male teacher new entrants are lower.

• The number of men in prison is now higher than it was in 2019 as are the number of boys excluded from school. The number of men in prison across the whole UK (over 93,000) now exceeds the capacity of Wembley Stadium.

This report recommends that policymakers, academics, employers, representative bodies and NGOs/third sector organisations should, where the data shows clear gender differences and/ or barriers, take a gender-sensitive approach to their policymaking and research.

This includes areas which this report has highlighted such as employment, education, health and crime. Current examples would include addressing male-specific challenges in the forthcoming Get Britain Working Plan, Industrial Strategy and Men’s Health Strategy. In addition, addressing boys’ relative educational underperformance would fit this model.

In future years, additional scorecard measures will be developed including across all four nations in the UK and covering a range of intersectionalities, including race and ethnicity. Feedback and views will be sought on these.

_1.webp)