This week, the UK’s call for evidence on parental leave closed, the case for reforming paternity pay is clear: fathers need longer, better-paid leave to support partners and families, and, strengthen the future workforce.

As the UK Government’s call for evidence on parental leave and pay closed (UK Government, July, 2025), attention is turning to what happens next.

Nick Isles (CPRMB, June, 2025) rightly set out the case for learning from the Nordic experience: longer, well-paid paternity leave that strengthens families, boosts equality, and ultimately benefits the economy. The question now is what additional evidence the UK needs for the future — and what arguments might persuade policymakers to act.

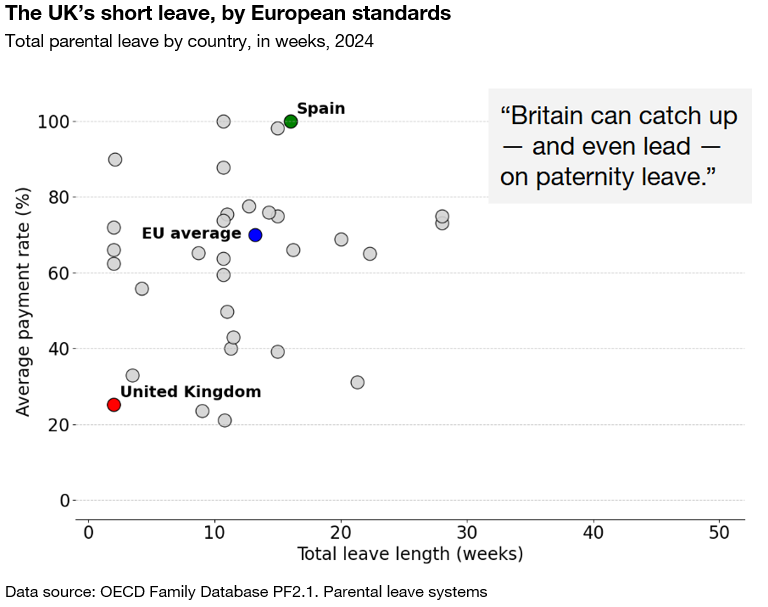

One immediate lesson worth repeating is that Britain risks falling further behind its peers if it doesn’t act decisively soon. While the UK still offers only two weeks at a statutory rate that is far below average wages, Spain has recently introduced 16 weeks of fully paid leave for fathers (Reuters, July, 2025). It is not surprising that uptake lags so badly. In fact, past government survey data shows that 35% of UK fathers who did not take leave cited affordability as the reason, compared with just 11% of mothers. The system as it stands is neither generous enough nor fair enough to encourage fathers to use it.

Thankfully, the government already seems to be aware of much of the existing evidence (UK Government, July, 2025). Yet, what is striking about the evidence base provided by the government is what it leaves out. It covers immediate objectives such as health, equality and childcare, but says little about the long-term gains of greater parental, specifically, paternal involvement. These matter.

Studies consistently show that fathers who take leave remain more engaged in childcare over the long run (Tamm et al., Aug, 2019). That strengthens family relationships, supports children’s development, and is even linked to lower rates of youth crime.

At the macro level, it can encourage more women back into the workforce, which helps reduce the gender pay gap, and raise household incomes. Public finances can benefit too: with more parents in sustained employment, tax receipts rise and reliance on childcare and welfare support falls.

Data source: OECD Family Database PF2.1. Parental leave system

Nor should we assume that extending paternity leave would harm men’s wages or career progression. Emerging evidence from Norway suggests no long-term penalty (Corekcioglu et al,. Oct, 2024).

On the contrary, when leave is well-paid and ring-fenced, fathers take it, families thrive, and economies grow.

Importantly, culture matters as much as cost, alongside making connections to the broader societal context. Recent research highlights that women are increasingly delaying having children, but when they do, the presence of a supportive partner may be the most important factor in that decision (Oxford, Dec, 2024). Yet without proper time off, fathers are denied the opportunity to play that role from the very beginning. A policy designed for the 1970s is simply not fit for the 2020s.

So what should be done? The Women and Equalities Committee has already recommended six weeks at 80% of pay (WEC, Jun, 2025). That is a welcome starting point, but it should be strengthened further. Leave must be paid at least at the Living Wage so that no family is priced out. Entitlements should be framed not as “benefits” but as investments in the future workforce.

And cultural change matters too: paternal presence should be built into recently updated relationships and sex education (The Education Hub, Jul, 2025) so that new generations see caregiving as a responsibility shared equally between mothers and fathers.

Britain’s parental leave system was built for another era. Reform is overdue. As the call for evidence closed, the government must decide whether it wants to continue with symbolic entitlements that most fathers cannot afford to use — or whether it is ready to invest in a modern system that pays for itself in the long run.

References

Corekcioglu, G., Dahl, G. B., & Løken, K. V. (2024). Long-term effects of paternity leave on wages: Evidence from Norway. Economics Letters, 238, 111762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2024.111762

Isles, N. (2025, June). Paternity pay: Lessons from the Nordics. Centre for Progressive Reform for Men and Boys (CPRMB). https://menandboys.org.uk/paternity-pay-nordic/

Oxford University. (2024, December 10). Expert comment: Why are people in the UK leaving it so late to have children? University of Oxford News. https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2024-12-10-expert-comment-why-are-people-uk-leaving-it-so-late-have-children

Reuters. (2025, July 29). Spain’s new parental leave gives fathers one of Europe’s most generous allowances. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/spains-new-parental-leave-gives-fathers-one-europes-most-generous-allowances-2025-07-29/

Tamm, M., Cools, S., & Fiva, J. H. (2019). Fathers’ quotas and fathers’ involvement: Evidence from a natural experiment. Journal of Population Economics, 32(4), 1361–1394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2019.04.001

The Education Hub. (2025, July 21). New RSHE guidance: What parents need to know. GOV.UK. https://educationhub.blog.gov.uk/2025/07/new-rshe-guidance-what-parents-need-to-know/

UK Government. (2025, July 3). Parental leave and pay review: Call for evidence. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/calls-for-evidence/parental-leave-and-pay-review-call-for-evidence/parental-leave-and-pay-review-call-for-evidence#introduction

Women and Equalities Committee. (2025, June 10). Equality at work: Paternity and shared parental leave. House of Commons. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5901/cmselect/cmwomeq/502/report.html

_1.webp)